“We need to have more conversations about organ donation”

Paula Massie from Aberdeen received a double lung transplant in 2019, ten years after being diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH). She is sharing her story to mark Organ Donation Week 2020 and to get people talking about this important issue – no matter how uncomfortable it feels.

“I was 29 when I was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension and I had my first transplant assessment three years later, but it wasn’t the right time. I was assessed again every two years and in 2018, following a sudden deterioration, I was put onto the list.

After eight years of stability I was declining. I was really poorly; I couldn’t even walk to my kitchen, I couldn’t breathe, and my heart was four times the size it should have been. In fact, I was almost deemed unsuitable for transplant because of how enlarged it was.

The doctors at the Freeman Hospital in Newcastle, where I was treated for my PH, really put my mind at rest when I was listed. They were very open and honest about the risks, and the recovery. I knew it would be a rough journey, but I was prepared for it and I had confidence they were making the right decision for me at the right time.

New lungs, new life

I was told that for my blood type, the average wait for organs is about two years so I decided to try and get on with day-to-day life and not spend my time simply waiting.

I continued working as classroom assistant for the first few months, until I became too ill, and it was only when I had a false alarm that things began to feel real.

That call came nine months after I was listed, and I waited a long time in the hospital before finding out the lungs were not suitable. I was upset, but it prepared me for when the next call came three months later.

When that one came, I was sleeping. It was 2am on 9th May 2019 and before I knew it there was an ambulance at my door and I was then being flown down to Newcastle by air ambulance. It was all so quick.

At the hospital, there was a 12-hour wait until the operation. As the day went on, I was thinking it was unlikely it would go ahead, even though I was kept well informed about the tests that were happening. It was only when I was actually taken down to theatre that I was sure the transplant would go ahead.

It’s odd because I’m normally a nervous wreck with operations and medical procedures but I had never felt so calm. I think I was at the point that I felt so ill, so awful, that I was just relieved I was getting the chance to feel better.

I was in surgery for eight hours and there were some complications, so I was in and out of theatre a few times. I must have been the doctors’ worst nightmare! But the transplant was a success and I was taken to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) to begin my recovery.

Getting stronger

I was on ICU for seven weeks and it was quite scary at the beginning. I had hallucinations – which I believe are quite common – but I was looked after so well. I had an issue with numbness in my legs, which meant I had to learn to walk again, but although my recovery wasn’t the smoothest it was all worth it.

Immediately after I woke from the operation, I noticed a difference. My lips, which had always been really dry, instantly felt better and the colour of my skin had improved. I couldn’t stop looking at my hands; the skin texture and everything had changed.

At one point during my time on ICU the nurses took me outside in my bed, just to get some fresh air, and it was amazing. It was raining, and I just lay there thinking how good it felt being able to breathe.

My family visited me regularly, including my husband and our foster son – who was fantastic throughout it all.

After seven weeks I was moved to a lower dependency ward, where I was encouraged to go for walks outside, and then into a ‘recovery flat’ attached to the hospital. Eventually, three months after the operation, I was allowed home – and it was here I felt my recovery accelerated.

Life is so different now. I can now enjoy going for a walk, rather than everything feeling a chore like it did with PH. I always had that tight squeezing feeling and at one point you could see my heart beating through my armpit. Now it has shrunk back to the size it should be. It’s quite amazing.

I’ve even been quad biking, and not having the pump or having to make up medicine all the time – and deal with the side effects – feels amazing. Now I can just take my anti-rejection tablets and get on with my day. It’s given me a freedom I didn’t have before.

Although I’ve been left with some wheezing, I’ve only had minor problems with rejection and the incision wound hasn’t caused me any issues. I have a seven-inch long scar and I feel proud of it. It’s a sign of what I went through, a challenge I overcame, and I don’t want to hide it away.

Finding the right words and having the right conversations

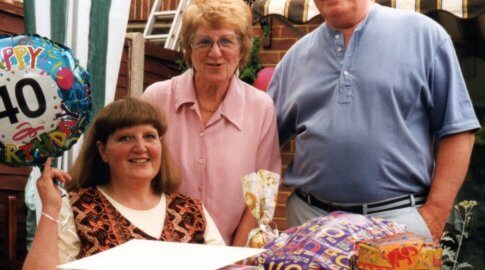

I turned 40 in January this year, with new lungs. I always used to joke with my doctors that life began at 40, so that’s when I wanted my transplant. Without it, I don’t think I would have reached that milestone.

It felt amazing not only to see that birthday, but to feel well enough to celebrate it too.

All I know about my donor is that she was a woman who was 56 when she died. I recently wrote to her family, as lockdown felt like the right time, and now I just have to wait and see if they want to write back.

There are no words that can describe how much I appreciate the gift my donor gave me and that’s what was so hard about writing the letter – the words ‘thank you’ are just not enough. She gave me a life.

In March next year the opt out – or ‘deemed consent’ – system will come into force in Scotland (it’s already in place in England and Wales). This means that unless you declare otherwise, you will be deemed to have no objection to your organs being donated after you die – but what many folk don’t realise is that it’s still the family who are able to have the final say. And that’s why having conversations is so important.

Organ donation is a subject people don’t seem to like talking about; they seem uncomfortable speaking about death. But we need to start having these conversations, as it’s going to happen to all of us eventually.

If we talk about it, we can find what people’s views are. It must be very difficult for a family having to make a decision about a loved ones organs without knowing what they would have wanted.

It’s about removing that fear, and it’s about educating people about the benefits of organ donation. It’s an uncomfortable thing to talk about but the more we do it the more it will become normalised.

Helping others

Having a transplant is quite isolating because some folk think ‘that’s it, you’re cured’, but it’s not as simple as that. It’s a lifetime of going back and forth to clinics, for checks, and watching everything. A doctor told me it’s like trading one thing for another, and you’re certainly not free from hospital appointments.

It’s good to tell people the positives of transplant but it’s also important that people are aware of the complications too. But if you’re living with pulmonary hypertension you’ve already been through a lot – so you’re strong enough to deal with a transplant if it comes to that.

As well as raising awareness of organ donation I’m now trying to set something up to support other people going through transplant. When I came back home from hospital I realised how little there was around me in the way of support groups, but I’ve managed to link in with people by sharing my story in my local paper.

I don’t have pulmonary hypertension anymore, but I still want to help people who do. I’ve made so many friends through the PHA UK Facebook group and it has been a lifeline.

It was actually through that group that I realised transplant was an option for some people with PH, as I watched others going through the journey. I don’t remember my medical team mentioning it to me when I was first diagnosed as I was concentrating on coming to terms with the diagnosis and learning to live with IV medication. I now really want to support other people with PH who may be facing a transplant.”

- If you would like to contact Paula about her transplant, please email media@phauk.org and we will pass on your message.