“The thought of my first cycle ride post-op still brings tears to my eyes”

For years, Rachel Bain was told her symptoms were down to anxiety – until finally, a diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) led her to a pulmonary endarterectomy that would give her back her life. Six months after surgery, she looks back on her journey and celebrates being able to cycle in the Kent countryside once again…

“’You’re out of breath’ the caretaker said laughing as he watched me carry a box up a short flight of stairs. He was right, though I hadn’t noticed it, and I shouldn’t have been short of breath at all.

That was in September 2018 and shortly after that I noticed other little things, like how I slightly struggled to keep up in walking long distances with my husband and teenage sons, and how cycling up hills that I’d cycled up for years were becoming a struggle.

In November 2018 I went to the doctors and was sent for tests, all of which I was told were normal. By early 2019 my breathlessness was more noticeable, and my new diagnosis from the doctor was ‘breathlessness due to being overweight and panic attacks’.

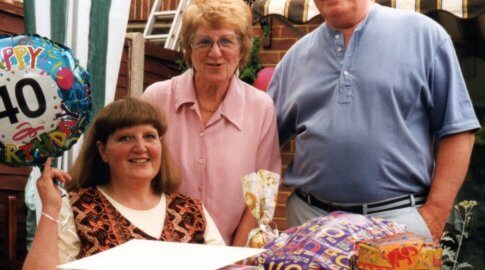

But my weight hadn’t changed and though overweight I was fit; I played racketball and cycled around 60 miles a week, and had successfully cycled London to Paris and then London to Amsterdam and onto Brugge only nine months earlier (pictured below).

As my mother had died in 2018, I assumed this was causing anxiety, so I paid for bereavement counselling, but my symptoms just got worse and worse. In August 2019 I went back to the doctor as I now had blood tests showing declining kidneys and massively swollen ankles. I was still diagnosed as having anxiety.

I had cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) counselling on the NHS and even tried hypnotherapy to overcome the anxiety that I never actually had.

Of course I now know that I, like many others suffering from CTEPH and pulmonary hypertension, was just being continually misdiagnosed.

Even though I walked at a snail’s pace, had to sit on the bed for five minutes at the top of the stairs and feared even the slightest incline – with the smallest of undulations feeling like a mountain – I was still told it was anxiety.

In fact, it wasn’t until three years after my symptoms started that a different doctor at the surgery finally listened to me and sent me to a cardiologist, who found I had an enlarged right heart ventricle.

Unfortunately, the private healthcare chest scans ordered by the cardiologist weren’t reviewed until after I was taken into hospital with pneumonia – where I was rescanned and finally diagnosed with possible CTEPH.

Although it was a relief to know I wasn’t going mad, it was a rather scary moment, as were the four months or so that followed.

The respiratory doctor at the hospital was great, initiating tests to try and find out why I was creating so many blood clots (though I still don’t have an answer to this and probably never will) and referring me to Royal Papworth Hospital for review.

This hospital was fantastic, as was the PHA UK, who helped answer lots of questions I had over the coming months.

Following a right heart catheterisation, I was formally diagnosed with CTEPH and told I was possibly eligible for a pulmonary endarterectomy (PTE surgery). Even though the thought of the surgery was terrifying, it was music to my ears!

I’d already read all about PTE and at that point plucked up the courage to watch the BBC documentary featuring the surgery.

Soon after, I meet the team at Royal Papworth to go on through the details of the surgery and be added to the list.

At this point I focused on one thing; climbing back onto my road bike that hadn’t been touched for over a year, and once again cycling through the delightful Kent countryside.

I had the PTE surgery in December 2021 and I’m writing this just six months on from the surgery.

My recovery has gone well. I followed advice and started by walking back and forth along the garden patio within a week of surgery to keep mobile. Within two weeks I was doing a half-mile lap around the local park.

The friends who had sympathetically walked and exercised with me, even when I’d become really slow, helped by being in a weekly rota to ensure I had someone to walk with every day.

By the end of the first three months post-op I was walking two to three miles every single day without having to stop to talk or catch my breath and at a speed I hadn’t managed for nearly three years.

After my three-month checks I started to cycle indoors on a turbo trainer [a device that keeps your bike stationary] for very short intervals, building up to my first ride out at the end of April with my husband.

After just a few minutes I started to cry out of sheer happiness. This was the moment I had focused on to get me through surgery.

I was back on my bike and not stopping every five minutes to catch my breath or feeling like I was going to die. In fact, it was the opposite – I felt truly alive, ecstatic that I could enjoy something so simplistic as to ride a bike again. Before, I thought I’d never do it again.

The thought of that day, my first cycle ride post-op, still brings tears to my eyes! I will be forever grateful to Mr Jenkins, Dr Cannon and the fantastic team at the Royal Papworth Hospital for giving me back my life.

Finally, I would also like to add that I think this journey of illness, surgery and recovery is just as hard, if not harder, for those closest to you. I cannot thank my family and friends enough for their continued support.”